1. Introduction

When drafting international contracts, a matter of particular concern is to focus on unforeseen circumstances that may lead to substantial problems and cost. Questions may arise, such as:

- Who will be responsible if a ship with urgent cargo for a construction site is damaged by a heavy storm and the cargo is lost?

- Who is responsible for the delay in completing the construction work and substantial penalties that might incur?

| Due to recent events, we included a case study in this newsletter to examine the effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on contractual obligations. |

Force majeure applies to cases where performance has become (temporarily) impossible due to an event beyond one party’s control although all reasonable precautionary measures had been taken.

Hardship deals with cases where the agreed performance is basically still possible. However, some underlying facts have substantially changed, so that proper fulfilling of the contractual obligations is still possible in principle, but does not make any economic sense.

It is important to understand that force majeure and hardship are two different principles, even if they sometimes are treated as the same. They are different in their preconditions and in their legal consequences. To apply force majeure to a case, the legal obligations of a party must become impossible for everybody due to circumstances that nobody can avoid (e.g. caused by a major earthquake).

The English translation of force majeure is “act of god”, indicating that such circumstances cannot be foreseen. However, precautionary measures may be necessary (e.g. if a factory is near the sea, the owner must be prepared for certain levels of flooding).Hardship, in contrary, is based on the fact that the underlying circumstances of the contract change in a way the parties did not foresee at the time of concluding the contract, and although in principle the contractual obligations are still fulfillable, it does not make sense from an economic viewpoint. Example: The seller of a specific object looses the object in the ocean. In principle, he must try to recover it from the bottom of the ocean, which is theoretically possible, but obviously does not make economic sense.

The legal consequences of both doctrines are very different. Consequence of force majeure is that one party cannot fulfil its contractual obligations (impossibility) and is therefore relieved from such obligations during the time of force majeure. The legal consequence of hardship is that the party for which the underlying circumstances did change substantially can basically still fulfil its contractual obligations and perform the contract, but the performance became economically worthless.

Depending on the contractual agreement between the parties or the material law and/or the agreed legal consequences with regards to force majeure or hardship, the contract will be adjusted to the circumstances automatically, or the parties will have to re-negotiate the contractual details that are affected by the changed circumstances (most likely the purchase price and delivery date).

Most national laws and international conventions contain provision on force majeure and/or hardship.

- The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (“CISG”) contains a force majeure clause, however, it does not contain any rules on hardship.[1]

- The principles of the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (“UNIDROIT”) contain provisions dealing with force majeure and hardship.

- The rules of the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) also contain provisions dealing with force majeure and hardship.

- There are various other contract terms issued by renowned international associations, such as the Fédération Internationale Des Ingenieurs-Conseils (“FIDIC”), which include a force majeure clause. It has to be noted that the FIDIC terms focus on contracts concerning construction and engineering projects.

2. Definition and Purpose

2.1 Force Majeure

Force majeure is French and stands for higher force. Force majeure means unavoidable events such as natural disasters of all kinds, especially storms, earthquakes, flood, volcanic eruption, but also fire, traffic accidents, kidnappings, wars, riots, revolution, terrorism, sabotage and strike. Force majeure regularly requires an unexpected occurrence of such events. However, a force majeure event has to be denied if the parties must expect such incident to happen, e.g. floods that occur repeatedly in the same region or fires in dry countries, and one party neglected to take the respective precautions. A force majeure event, therefore, could be generally described as an event that affects the contractual relationship unpredictably from the outside and that, despite the parties taking extreme care, was not avoidable.

The question remains who is responsible for the non-performance of the contract due to the force majeure event. In order to avoid disputes and risks of interpretation, force majeure clauses have been included in a great number of international commercial sources of law to essentially dispense both parties from liability or their obligations when an extraordinary event or circumstance beyond the control of the parties occurs. The occurrence of a force majeure event leads to the – at least temporary – suspension of the primary obligations of both contracting parties. Either party has to bear the adverse consequences of non-performance or the delay in performance. As a consequence, the liability dispenses and the other party is unable to claim compensation for damages.

2.2. Hardship

In case of hardship, the performance of the contract is not impossible, but hindered. Hardship is defined as any event of legal, technical, political or financial nature occurring after the conclusion of the contract, which was unforeseeable at the time the contract had been formed, despite using the utmost care. In general, hardship does not cause the impossibility of performance, but allows for renegotiation of the contract.

Hardship clauses typically recognise that parties must perform their contractual obligations even if events will render performance more difficult than one would reasonably have anticipated at the time of the conclusion of the contract. However, where continued performance has become excessively burdensome due to an event beyond a party’s reasonable control, a hardship clause can oblige the parties to negotiate alternative contractual terms. The purpose of a hardship clause is to provide a higher level of flexibility and to balance the risk between the parties.

The principle of hardship is particularly influenced by common law and the equitable rights of the Anglo-American legal system to find a balance under the principle of equity and good faith.

3. Force Majeure in Codified Law

3.1 Force Majeure in German Law

The term “force majeure” (“höhere Gewalt”) occurs in §§ 651a seq. BGB, which regulate the travel law. In addition, the idea of force majeure is also recognised in § 275(1)-(3), § 326(1), (5) and §§ 323 seq. BGB.

Example:

A vendor and a purchaser conclude a contract on the delivery of five tons of specific rice. The vendor sorts out those five tons and stores them in another (well-built) warehouse ready for delivery. Due to an exceptionally heavy storm, the warehouse and the rice are destroyed during the night.

Solution:

The rice is destroyed because of the storm. This is an unavoidable event of superior power which the parties could not have foreseen at the time of the conclusion of the contract. As the vendor already finished the ascertainment of goods by sorting out the rice and storing it in another warehouse, the performance of the delivery of exactly these five tons of rice is now impossible for the vendor and everyone else, § 275(1) BGB. Accordingly, the right of the purchaser to demand delivery is barred by this, § 275(1) BGB. On the other hand, the vendor cannot claim damages, § 326(1) BGB. The purchaser has the opportunity to withdraw from the contract, § 326(5) BGB, without having to set a time limit. Thus, the performances exchanged have to be returned, e.g. the deposit the purchaser had to pay.

3.2 Force Majeure in French Law

Force majeure is defined by the Art. 1218 of the French Civil Code as follows:

“The occurrence of an event which is beyond the control of the obligor, which could not have been reasonably foreseen at the time of the entry into the contract and the effects of which cannot be avoided by appropriate measures and which prevents performance of its obligation by the obligor”.

This definition requires only irresistibility and unpredictability. If the effects are temporary, the performance of the obligation is suspended unless the delay resulting therefrom justifies termination of the contract. If the effects are permanent, the contract is automatically terminated, and the parties are discharged of their obligations.

3.3 Force Majeure in US Law

In US Law there is no codified definition of force majeure. The enforceability of force majeure clauses is highly dependent on the specific state law, the wording of the clause and the court’s interpretation. Therefore, companies must be aware of how force majeure clauses are interpreted and enforced in the particular state. Nevertheless, as the US contract law supports the principle of freedom of contract, so it is a good idea to implement a force majeure clause as it is mostly not construed into a contract by the courts.

3.4 Force Majeure in Thai Law

Section 8 of the Civil and Commercial Code of Thailand defined force majeure as follows:

“Any event the happening or pernicious result of which could not be prevented even though a person against whom it happened or threatened to happen were to take such appropriate care as might be expected from him in his situation and in such condition.”

Apart from that, force majeure is mentioned and recognized by other laws as well, such as the Civil Procedure Code. Moreover, common contract templates used in the country usually include force majeure clause. Within the limitation of the law, e.g. the Unfair Contract Terms Act, the parties may agree to define certain circumstances as force majeure in their contract.

3.5 Force Majeure in Vietnamese Law

Art. 156 of the Civil Code defines force majeure as follows:

“An event which occurs in an objective manner which is not able to be foreseen and which is not able to be remedied by all possible necessary and admissible measures being taken.”

The consequences of force majeure are stipulated in Art. 420 para. 2 and 3 of the Civil Code:

“2. Where circumstances change substantially, the party whose benefits are affected has the right to request the other party to re-negotiate the contract within a reasonable period of time.

- Where the parties are unable to reach agreement on amendment of the contract within a reasonable period of time, either party may request a court to:

(a) Terminate the contract at a definite time;

[…]”

3.6 Force Majeure in the CISG

3.6.1 About the CISG

CISG is a treaty offering an uniform international sales law that has been ratified by 93 countries. This makes the CISG one of the most successful international uniform laws. It should be noted, however, that the application of the CISG is often excluded by the parties.

3.6.2 Applicability

CISG law is directly applicable to contracts for the sale of goods between parties whose places of business are in different member states (Art. 1(1)(a) CISG). CISG is also applicable in case only one of the parties is a resident in a CISG member state and the contract between the parties refers to the material law of this state (Art. 1(1)(b) CISG). Even if neither party is resident in a member state, the CISG can be applicable when the parties expressly agree on its application for their legal relationship. CISG defines its own territorial criteria of application without the need to resort the rules of private international law. For sales contracts concluded prior to the ratification of the CISG, Article 100(2) CISG applies:

“This Convention applies only to contracts concluded on or after the date when the Convention enters into force in respect of the Contracting States referred to in subparagraph (1)(a) or the Contracting State referred to in subparagraph (1)(b) of article 1.”

3.6.3 Definition

According to Art. 79(1) CISG, a party is not liable for failure to perform any of its obligations if it proves that the failure was due to an impediment beyond the party’s control and that such party could not reasonably be expected to have taken the impediment into account at the time of the conclusion of the contract or to have avoided or overcome it or its consequences. If a party is able to prove these requirements, it is relieved from its liability of performance and the other party cannot claim any further rights.

3.7 ICC Force Majeure Clause 2003

3.7.1 About the ICC

The ICC is the largest, most representative business organisation in the world. Objective of the ICC is to promote international trade and to support international businesses to face challenges and opportunities of globalisation. By issuing contract rules, an efficient settlement of international transactions is promoted.

3.7.2 Definition

- 1 of the ICC Force Majeure Clause states that in order to be considered force majeure, there must be an impediment due to failure, (which is similar to Art. 79 CISG) . § 2 is designed specifically on the basis of Art. 79(2) CISG and is intended to make it clear that a contracting party can invoke the clause where a party fails to perform its duties towards the other contracting party because of non-performance of a third party. § 3 of the ICC Force Majeure Clause provides a list of force majeure events, which includes, for example, war, explosions, natural disaster, strikes etc. As a legal consequence, the party who fails to perform and claims force majeure will be relieved from liability without having to face any claims of the forfeiting party and the other party is released from their obligations as well.

3.8 Force Majeure in the UNIDROIT Principles

3.8.1 About the UNIDROIT

The UNIDROIT is an independent intergovernmental organisation. Its purpose is to study needs and develop methods for modernising, harmonising and coordinating private international law and in particular commercial law between states, and to draft international regulations to address the needs of the members. Membership of UNIDROIT is restricted to states adhering to the UNIDROIT Statute. UNIDROIT’s currently 63 member states represent a variety of different legal, economic and political systems as well as different cultural backgrounds.

3.8.2 Definition

The UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts 2010 contain a force majeure clause in Art. 7.1.7. This rule excuses non-performance by a party if such party proves that the failure was due to an impediment beyond its control and that it could not reasonably be expected to have taken the impediment into account at the time of the conclusion of the contract or to have avoided or overcome it or its consequences. The article does not restrict the rights of the party who has not received performance to terminate the contract if the non-performance is fundamental. Where applicable, it states to exclude the non-performing party from liability in damages. In some cases, the impediment will prevent any performance at all but in many others, it will simply postpone performance.

3.9 Force Majeure in the FIDIC Contract Samples

3.9.1 About the FIDIC

The FIDIC, the International Federation of Consulting Engineers, represents members of the engineering industry. As such, FIDIC promotes the interests of the construction and engineering industry. Founded in 1913, FIDIC today numbers 102 member associations representing approx. 1 million professionals. FIDIC also publishes international contract samples and business practice documents.

3.9.2. Definition

The “Red Book” (concerning construction contracts), the “Yellow Book” (concerning contracts on plants and their design) and the “Silver Book” (concerning EPC (Engineering, Procurement and Construction) contracts) all contain a force majeure clause in their Art. 19. The clause is a combination of a new provision for defined events of force majeure, and a new wording of a provision covering impossibility (or illegality) of performance. Clause 19.1. defines force majeure as an event beyond the control of the employer and the contractor, which makes it impossible or illegal for a party to perform, including but not limited to war, hostilities, rebellion, contamination by radio-activity from any nuclear fuel or riot.

4. Hardship Codification in Law

4.1 Hardship in German Law

- 313(1) BGB states that a contract must principally be renegotiated if an event occurs which fundamentally alters the present contract and places an excessive burden on one of the party’s performance making the adherence to the contract unreasonable. In case renegotiation is impossible, the disadvantaged party can withdraw from the contract. This hardship clause derives from the idea of good faith in § 242 BGB and restricts the basic principle “pacta sunt servanda”.

4.2 Hardship in French Law

Art. 1195 of the French Civil Code stipulates the following:

“If a change in circumstances that was unforeseeable at the time of the conclusion of the contract renders performance excessively onerous for a party who had not accepted the risk of such a change, that party may ask the other contracting party to renegotiate the contract”.

“The requesting party must continue to perform its obligations during the renegotiation. In the case of refusal or the failure of renegotiations, the parties may agree to terminate the contract from the date and on the conditions which they determine, or by a common agreement ask the court to set about its adaptation. In the absence of an agreement within a reasonable time, the court may, on the request of a party, revise the contract or put an end to it, from a date and subject to such conditions as it shall determine”.

The clause expressly states that it does not apply to a party who has assumed the relevant risk. Therefore, it is recommended that parties endorse wording specifically stating that risk of hardship is assumed.

4.3 Hardship in US Law

In the US contract law, there is no common definition of hardship. Nevertheless, hardship clauses can be used, but it is difficult to create the hardship if the relevant event is too vague. Therefore, a force majeure clause in combination with the requirement to firstly renegotiate the contract accomplishes what a hardship clause could provide in other legal systems.

4.4 Hardship in Thai Law

Since the principle of hardship is generally and originally adopted in common law legal system, Thai law, particularly the Civil and Commercial Code, only mentions force majeure. However, since a hardship clause does not contradict public order or good morals, it can still be agreed by the parties and added into the contract upon the doctrine of freedom of contract.

4.5 Hardship in Vietnamese Law

The concept of hardship is known under Vietnamese law and may under the freedom of contract be specified in contractual agreements

4.6 Hardship in CISG

The CISG does not contain a hardship clause, and the prevailing opinion is that Art. 79 CISG does not cover hardship. Renegotiation is therefore not an option.

4.7 ICC Hardship Clause 2003

Paragraph 1 of the ICC Hardship Clause recognises that parties must perform their contractual obligations even if

“events have rendered performance more onerous than would reasonably have been anticipated at the time of the conclusion of the contract.”

However, according to paragraph 2,

“if continued performance has become excessively onerous due to an event beyond a party’s reasonable control which it could not reasonably have been expected to have taken into account, the parties shall negotiate alternative contractual terms which reasonably allow for the consequences of the event.”

According to paragraph 3, the party invoking the hardship clause is entitled to terminate the contract in case alternative contract terms cannot be agreed upon.

4.8 Hardship in the UNIDROIT Principles

Art. 6.2.2 of the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts 2010 defines hardship as a situation where the occurrence of events fundamentally alters the contract, provided that those events meet the requirements which are laid down in subparagraphs. This also shows that Art. 6.2.2 is not exhaustive but has to be adjusted by the parties to fit their needs.

Under the UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts 2010, hardship has effects both in procedural and material law (Art. 6.2.3). The disadvantaged party can request renegotiation. If this party fails to do so, it does not lose this right. However, this failure may affect the finding as to whether hardship actually existed. If the parties fail to reach an agreement on how to amend the contract according to the changed circumstances within a reasonable time, Art. 6.2.3(3) authorises either party to resort to the court. Paragraph 4 provides legal consequences (termination/contract adaption) for the court to deliver judgement in these cases.

4.9 Hardship in the FIDIC Contract Samples

The major FIDIC contract samples do not contain hardship clauses. In large projects, where the performance of the parties’ contractual obligations is spread over several years, the parties might thus consider to add a hardship clause to the contract to stipulate when and how the parties will rearrange the contractual terms in the event the contract loses its economic balance.

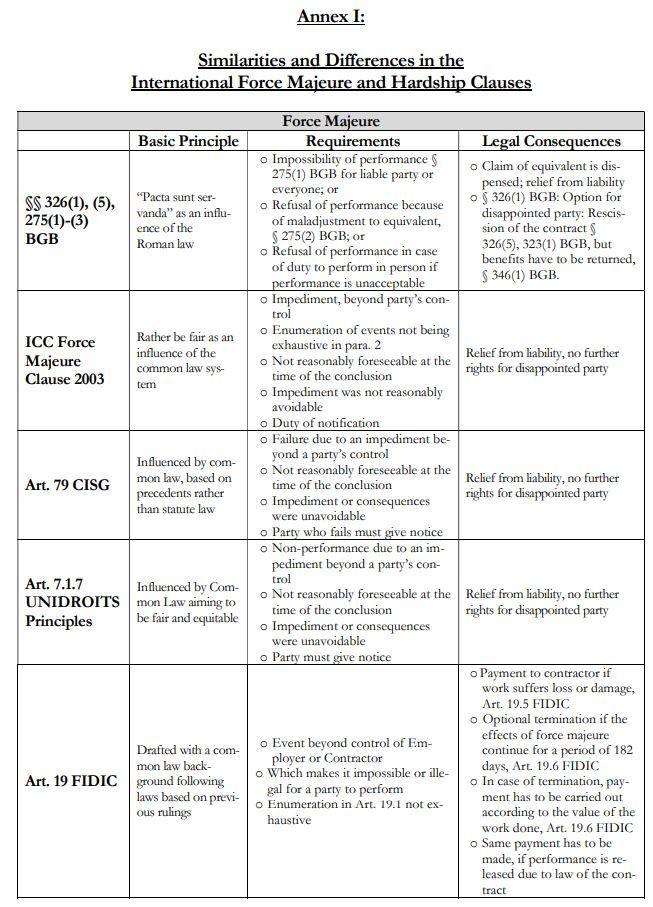

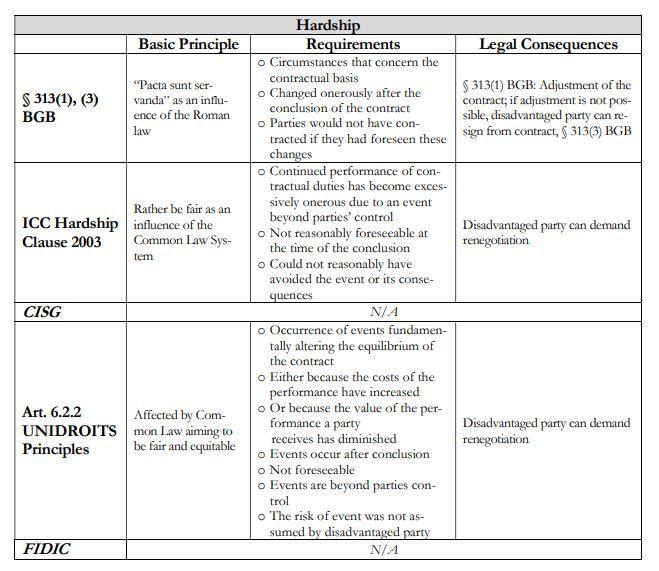

5. Similarities and Differences in the International Force Majeure and Hardship Clauses

Please refer to the table in Annex I.

6. Conclusion

The aforementioned rules and regulations are just examples for the variety of regulations available to deal with force majeure and hardship events. Due to this, the parties have to take a closer look at what they believe is necessary to be regulated in the contract itself. Different contracts need different clauses on diverse grounds. There needs to be an evaluation on what exact purpose the clause shall serve in the individual case.

7. Case Study: COVID-19 and Force Majeure

Due to the recent outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, questions relating to the failure of contractual performance have become particularly relevant. The World Health Organization (“WHO”) has announced on 30 January 2020 that COVID-19 constitutes a public health emergency of international concern. Thus, the question arises whether contractual parties affected by the recent outbreak of COVID-19 and/or corresponding government restrictions might be exempt from their contractual performance and/or liability under certain circumstances.

Due to governmental shutdown of factories and the quarantine of whole cities, many contracts cannot be fulfilled as agreed, as these measures led to severe disruptions to both inbound and outbound shipments. This impeded countless supply chains and may result in companies being unable to fulfil their contractual obligations.

Whether the outbreak of COVID-19 or any corresponding circumstances meet the contractual or statutory prerequisites to qualify as force majeure or hardship depends on the agreed contractual provisions, e.g. whether the contract provides for categories or defined events expressly qualifying as force majeure or hardship. Generally, it has to be assessed whether the outbreak was beyond the parties’ control and whether it has impacted performance to the extent required.

Force majeure is given if the clause does explicitly include disease, epidemic, quarantines or similar. Indeed, the outbreak of epidemics must not be seen as an unforeseeable event as the emergence of new viruses is a given scientific fact.

Nevertheless, the unheard scale of close- downs and the quarantine of many millions of people represents a unique situation.

The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (“CCPIT”) has set up an online platform in order to issue Force Majeure Certificates to qualifying applicants who can provide legitimate documents proving delays or cancellation of transportation and/or export contracts. According to CCPIT, this aims to “help enterprises minimize liability for contracts that cannot be fulfilled due to the epidemic and safeguard their legitimate rights and interests”.

It has to be noted, however, that such Force Majeure Certificates will only indicate but not prove the occurrence of force majeure or hardship.

[1] In a landmark decision, the Belgian Supreme Court (19 June 2009, case number: C.07.0289.N) therefore applied the UNIDROIT principles to close this loophole in the CISG, although UNIDROIT principles were not agreed upon between the parties.